Field Notes

Insights into Small Business as a Path to Economic Security for Parents Who are Returned Citizens

National awareness around centuries-old racial equity issues has been steadily increasing over the past several years. Thanks to the work of countless advocates, scholars, community leaders, and others, the broader public has become more aware of many long-standing patterns known all too well by generations of Black and brown communities. Meanwhile, many in the social sector have made their equity efforts more explicit and focused, e.g. equitable evaluation has become a field in itself. The latest ‘dual-pandemic’ of COVID-19 and greater exposure of racism in the justice system has helped drive record-setting recognition of issues around anti-Blackness, police brutality, mass incarceration and the 40,000 consequences of a criminal conviction, residential segregation, education and economic inequities, and many others.

In this environment, Root Cause partnered with the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF) and Justine Petersen to evaluate the Aspire Entrepreneurship Initiative, a small business pilot program for parents who are returned citizens. The purpose of this pilot was to demonstrate an alternate path to economic security for returned citizens who are parents of young children and challenged in obtaining family-sustaining traditional employment. The program was designed to help such individuals start or grow a business to earn a family-sustaining income and strengthen their ability to support their children’s well-being.

Nearly 200 small business owners, nearly three-quarters (73%) of whom identified as Black or African-American, participated in the Aspire pilot over three years. Their businesses spanned a wide range of industries including cosmetology, children’s entertainment, landscaping, contracting and home improvement, financial investments, real estate, auto mechanics and roadside assistance, tutoring, retail, fashion, and health and wellness.

Significant efforts have historically been devoted to supporting entrepreneurship and small business as a piece of the economic security puzzle. Significant efforts also focus on supporting people involved with the justice system, including workforce and business training while in incarceration and support for life as a returned citizen. And further efforts still provide supports to parents raising young children. We first worked with WKKF and JP to help shape the Aspire program model that works at the intersection of these three areas while addressing the common gaps in each.

WKKF asked Root Cause to conduct a purpose- and equity-driven third-party evaluation, which would tap existing evidence to inform the program model, deeply engage participants and program staff, strengthen the implementing partners’ capacity to measure and improve their work, gauge the program’s ultimate results for participants and their families, and generate learning and best practices for the field. In addition to the traditional number crunching, we conducted interviews and focus groups. We also attended group business classes and shared meals with participants, talked business (leveraging Root Cause’s own experience founding an urban small business accelerator). I still have a couple of t-shirts that I purchased from participating businesses at Aspire graduation ceremonies.

The comprehensive, purpose-driven approach of our evaluation illuminated several critical insights that challenged many of our given assumptions and common practices in the field. We hope these insights can inform similar efforts that aim to support entrepreneurship and/or returned citizens.

1. There are several gaps across efforts that support small business and entrepreneurship in general, and particularly for people who have been incarcerated.

Typical small business training for individuals who are incarcerated focuses on building skills to translate into a job, versus actually starting or growing a business. Many broader entrepreneurship programs emphasize didactic training for aspiring start ups, while lacking elements to get those businesses up and running or to achieve specified income targets. And programs supporting existing business owners tend to be industry-agnostic and rarely cater to the unique challenges of returned citizens and/or parents of young children.

2. Participants were driven by a need to both be part of, and to support, their families and communities.

Aspire participants noted significant value in having a group of peers in such a similar and unique situation as themselves. For many Aspire participants, their business was part of a mission to uplift both their families and their broader communities. Many cited the desire to leave a legacy for their children, and to hire other returned citizens once their businesses provided the opportunity to do so. At each group class and graduation ceremony, we heard most participant speakers emphasizing these desires, with some volunteering to take on additional roles to keep their cohorts connected over the longer term. In an environment where returned citizens face thousands of barriers to traditional employment, improving the business success of returned citizen entrepreneurs can serve as a lever to increase community-wide employment opportunities.

3. Small business is but one piece of a complex economic security picture.

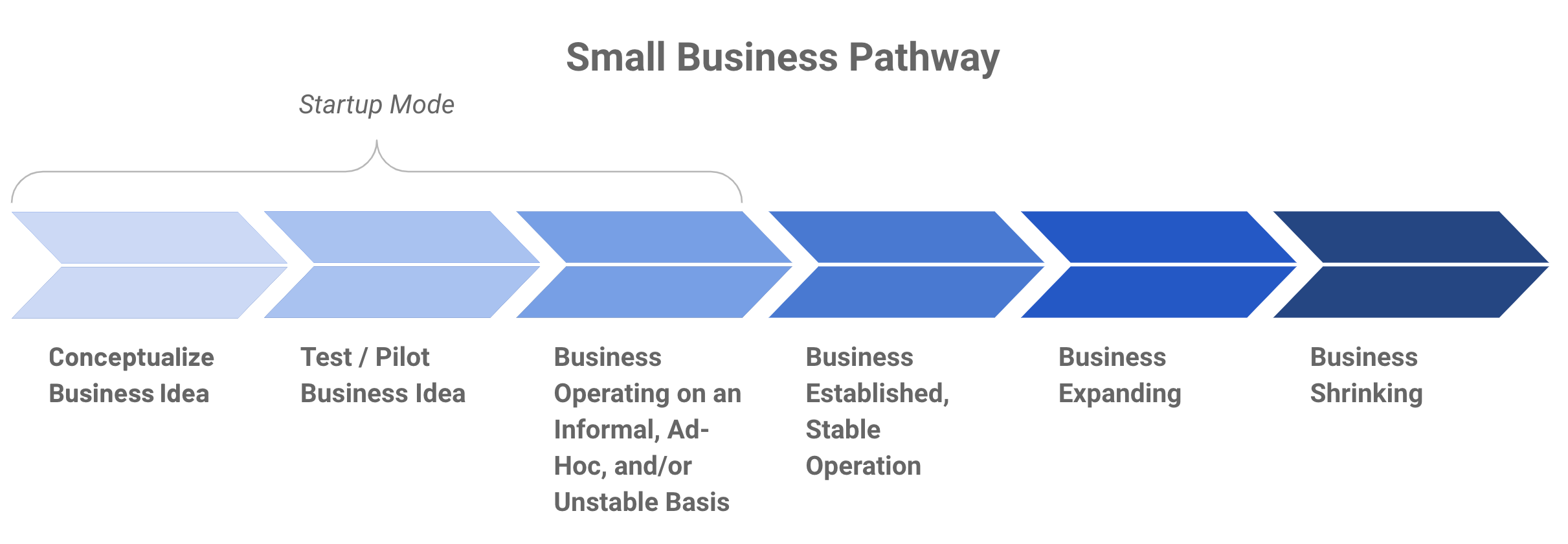

Root Cause and JP developed a Small Business Pathway to more accurately reflect participants’ evolution and nuances in starting and growing their small businesses, versus common lifecycle diagrams that reflect more high-growth ventures.

The Pathway, shown below, served as a central reference for the evaluation process to gauge how Aspire was helping participants move from one stage to the next.

The Pathway helped frame the real-life dynamics we observed, particularly how small business is often one of multiple efforts that people need to combine in order to generate sufficient income. Participants’ business efforts often occurred alongside traditional employment (which can itself include multiple jobs), as a kind of “side hustle.” And business efforts were often built around trying to expand a participant’s primary self-employment activity.

Partly because of this reality, there is often a blurry line between the pathway stages, and many factors hinder progress from one stage to the next. Advancing a small business along the pathway is hard, even in the best of circumstances, let alone considering the literally thousands of barriers faced by returned citizens and those who are parents.

These dynamics have particular implications for any small business efforts that aim to help individuals expand their business enough to generate family-sustaining income.

4. Later-stage businesses have an advantage.

Given the dynamics described above, participants experienced Aspire vastly differently based on which stage they began the program at. Those further along the small business pathway typically (but not always) had the advantage of being able to focus more on business specifics, such as refining marketing strategy or pricing, and were positioned to make faster progress. On the other hand, participants at earlier stages typically spent more time on exploring and confirming a business idea to pursue, or on making the transition from informal to more formal and stable business activity.

5. Industry matters.

The nature of each industry naturally led to widely varying implications for the need and use of financing, customer market size, competition, staffing, and numerous other areas. Thus, the reality of advancing each business along the pathway to achieve a family-sustaining income looked different for participants in each industry.

The range of industries affected peer group dynamics as well. While there were many points of collective understanding and peer learning across the many business types of Aspire participants, participants in similar industries were better able to trade specific notes.

6. For entrepreneur-parents, business and parenting skills are surprisingly related.

The Aspire program successfully integrated parenting and family content into an otherwise finance- and entrepreneurship-focused program. The content enabled participants to walk through building core supports such as social-emotional skills, parental resilience, social connections and networks, and the ability to tap into professional and social services when needed.

Participants found this combination to help address their multiple, overlapping challenges associated with returning from incarceration to their parenting, financial, and community roles. This is significant considering that participants cited family and personal needs as a top challenge holding them back from making further progress on their business, second only to accessing credit. Participants also noted that the connection between business and parenting skills was not evident at the beginning of the program, but became more apparent as the group classes progressed.

Considering the deep content learning generated via the process, we felt the significant value in lifting up the voices and experiences of participants when evaluating a program, and doing so with authenticity and humility. The evaluation approach more meaningfully involved people who might traditionally be seen only as “marginalized” and passive recipients of services, instead recognizing their level of inherent leadership and expertise.

The entire evaluation approach first considered the broader systems and equity context that it was conducted in. And the approach enabled more qualitative and continuous learning that was directly used to benefit the Aspire program and its participants. Through the process, WKKF and JP were able to solidify a more equitable, participant-oriented, and improvement-driven third-party evaluation approach to employ in the future and can be readily applied to other efforts in this field.

Too often, we see third-party program evaluations channel their full energy toward long, academic reports with broad stats suggesting a binary “effective”/”ineffective” label in the name of avoiding wasted funding. On the other side of the evaluation coin, qualitative evaluations may engage program participants only superficially and land on conclusions too broad to meaningfully inform program design and improvement.

To us, both of these approaches may be neglecting to ask “why” the evaluation is being undertaken in the first place, and can miss the opportunity that evaluations can provide for communities. Our evaluation was less about assigning an effective/not effective program label, and more about learning about participants’ lives and tapping their expertise to shape the Aspire program and broader systemic efforts to best support their economic security goals for their families.

Black communities and communities of color deserve better from the social sector that claims to serve their needs. We believe this evaluation approach marks a step in the right direction.